Is Working Hard a Racial Ideology?

Written by Ryun Chang

Disclaimer: My view expressed here does not necessarily represent the respective views of other AMI pastors.

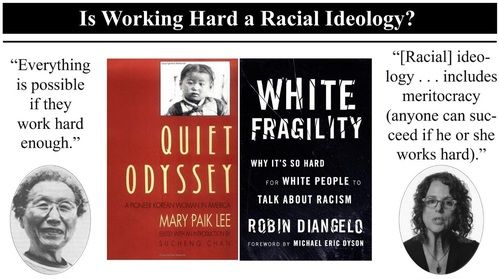

Little did Mary Paik Lee know that her memoir, "Quiet Odyssey: A Pioneer Korean Woman in America" (1990), allegedly contains an idea that, according to Robin DiAngelo’s bestseller "White Fragility" (2018), can “cause the most daily damage to people of color” (5). Really? Lee’s book tells the story of what life was like for a Korean family that went to Hawaii for work in 1905 (part of the original immigrants numbering around 7,000), and a year later moved to the Pacific Coast. A 5-year old when Lee left Korea, she went on to live 90 more years in America.

Initially written as a 65-page autobiography, it caught the attention of Sucheng Chan, an esteemed Chinese American historian, who was “prompted by her story’s intrinsic merit and its unique historical value” (135). Chan edited the book extensively for historical accuracy and expanded it to 134 pages.

The first time they met, Lee, then 86-year old, told Chan, “These things I’ve written down . . . I remember them because they made me suffer so.” Recalling her parents, Lee said, “Years of backbreaking work without enough food and relaxation took its toll on my parents, but they just hung on through sheer will power. Their wretched physical condition was painful to see” (134). Making life worse was virulent racism Asians faced in those years. Once, in 1918, as Lee was about to enter a church for Sunday service, the pastor told her, “I don’t want dirty Japs in my church . . . Go to hell” (54).

Even so, DiAngelo the antiracist would likely balk at what Lee writes at the end while reflecting on how well the third generation of her family was doing in America. After noting that her children, nieces, and nephews “are all well educated and work in responsible positions” (doctor, lawyer, banker), Lee says, “The third generation of [Asians] are fortunate to be born into a different world, where everything is possible if they work hard enough” (129).

If that statement went down smoothly, obviously you’ve not read "White Fragility" in which DiAngelo says this about working hard: “The system of racism begins with ideology, which refers to the big ideas that are reinforced throughout society . . . Examples of ideology in the U.S. include . . . meritocracy (anyone can succeed if he or she works hard)” (21). Finding this line of thought disruptive, she says, “these narratives allow us to congratulate ourselves on our success within the institutions of society and blame others for their lack of success” (27).

To antiracists, this meritocracy turns into a racial ideology when Black and Brown people are told that if they work as hard as, for instance, Asian Americans, they could be as successful—thereby implying that the playing field has levelled. Thus, DiAngelo wouldn’t be enamored with Lee’s faith in the American system that, she believes, rewards hard work, because, to DiAngelo, it continues to "privilege whites as a group" (24).

What should we do then? Actually, DiAngelo’s idea isn’t new. In 1988 Peggy McIntosh, in her seminal work, “White Privilege and Male Privilege,” suggests that we “must give up the myth of meritocracy [because] this is not such a free country; one’s life is not what one makes it; many doors open for certain people through no virtues of their own” ("Race, Class, and Gender", 76).

Before dismissing their ideas as coming from the Far Left, note that Tim Keller, now retired pastor of Redeemer Church in Manhattan, would likely agree with DiAngelo and McIntosh on meritocracy. Basing his thought on Malcolm Gladwell’s "Outliers: The Story of Success" (2011), Keller says, “Yes, hard work and aptitude is very important if you are going to succeed, but those are actually a small part of the whole because there has to be circumstances, timing, your upbringing, your culture and opportunities—all these things have to line up or you are not a success . . . [Whether] you are a success or failure is not mainly due to your hard work or lack of it . . . [It] depends on forces beyond your control.” Mary Paik Lee would be rolling in her grave just about now.

No doubt we all want to succeed but there are obstacles beyond our control, including racial discrimination for people of color, that stand in our way. Yet, the solution is rather simple: relinquish meritocracy. This isn’t because McIntosh recommends it but rather Scripture demands it: “What do you have that you did not receive? And if you did receive it, why do you boast as though you did not?” (1 Cor. 4:7). Recognize that what we have is not earned but God, in His inexplicable grace, gave to us. Sure, we work hard to reach our goals, believing with every ounce of our being that “all hard work brings a profit” (Prov. 14:23), but so did many others who, for reasons outside of their control, couldn’t get there. Only then will we see, as DiAngelo points out, the futility of congratulating ourselves on our success, and, instead of snubbing those who are still on the outside looking in, we will be “generous on every occasion” (1 Cor. 9:11).

As for those feeling overwhelmed by obstacles beyond their control, you also must renounce something: the idea that working hard is a means to get ahead. Rather, accept that working hard is the end in itself. This, of course, is a ridiculous concept unless you believe in the God of the Bible who demands stewardship of what has been entrusted—whether little or much is irrelevant—to us. What is relevant is that God will “settle accounts with [us]” on the judgment day, not based on how much we gained (which can be done in ungodly manners) but that we worked faithfully, regardless of whether it resulted in a profit (1 Cor. 4:2; 2 Tim. 4:16).

So, I break with DiAngelo who insinuates that incentivizing working hard is unavoidably a racial ideology. It could be but not intrinsically, especially for those who believe in God. We work diligently to honor God who values work itself. Note that it was before the fall that God “put [the first human] in the Garden of Eden to work it and take care of it” (Gn. 2:15). Our incentive is to glorify such God with diligent labor, whether manual or intellectual. Only then we hope to be that “hardworking farmer” [who is] the first to receive a share of the crops” (e.g., Lee's family; 2 Tim. 2:6). If not, we'll be okay, in time, knowing that God was pleased with our faithfulness.

And because we recognize that the playing field hasn’t quite leveled yet—but certainly not anywhere near the level of pre-Civil Rights era—the advice of Stephen Carter, a long-tenured Black law professor at Yale, should be heeded by all, not just people of color. He said, “It would not be a bad thing at all for us as a race to develop as our defining characteristic: Oh, you know these Black people, they always work twice as hard as everybody else.” Mary Paik Lee would have nodded her head in approval while also seeking changes.

Initially written as a 65-page autobiography, it caught the attention of Sucheng Chan, an esteemed Chinese American historian, who was “prompted by her story’s intrinsic merit and its unique historical value” (135). Chan edited the book extensively for historical accuracy and expanded it to 134 pages.

The first time they met, Lee, then 86-year old, told Chan, “These things I’ve written down . . . I remember them because they made me suffer so.” Recalling her parents, Lee said, “Years of backbreaking work without enough food and relaxation took its toll on my parents, but they just hung on through sheer will power. Their wretched physical condition was painful to see” (134). Making life worse was virulent racism Asians faced in those years. Once, in 1918, as Lee was about to enter a church for Sunday service, the pastor told her, “I don’t want dirty Japs in my church . . . Go to hell” (54).

Even so, DiAngelo the antiracist would likely balk at what Lee writes at the end while reflecting on how well the third generation of her family was doing in America. After noting that her children, nieces, and nephews “are all well educated and work in responsible positions” (doctor, lawyer, banker), Lee says, “The third generation of [Asians] are fortunate to be born into a different world, where everything is possible if they work hard enough” (129).

If that statement went down smoothly, obviously you’ve not read "White Fragility" in which DiAngelo says this about working hard: “The system of racism begins with ideology, which refers to the big ideas that are reinforced throughout society . . . Examples of ideology in the U.S. include . . . meritocracy (anyone can succeed if he or she works hard)” (21). Finding this line of thought disruptive, she says, “these narratives allow us to congratulate ourselves on our success within the institutions of society and blame others for their lack of success” (27).

To antiracists, this meritocracy turns into a racial ideology when Black and Brown people are told that if they work as hard as, for instance, Asian Americans, they could be as successful—thereby implying that the playing field has levelled. Thus, DiAngelo wouldn’t be enamored with Lee’s faith in the American system that, she believes, rewards hard work, because, to DiAngelo, it continues to "privilege whites as a group" (24).

What should we do then? Actually, DiAngelo’s idea isn’t new. In 1988 Peggy McIntosh, in her seminal work, “White Privilege and Male Privilege,” suggests that we “must give up the myth of meritocracy [because] this is not such a free country; one’s life is not what one makes it; many doors open for certain people through no virtues of their own” ("Race, Class, and Gender", 76).

Before dismissing their ideas as coming from the Far Left, note that Tim Keller, now retired pastor of Redeemer Church in Manhattan, would likely agree with DiAngelo and McIntosh on meritocracy. Basing his thought on Malcolm Gladwell’s "Outliers: The Story of Success" (2011), Keller says, “Yes, hard work and aptitude is very important if you are going to succeed, but those are actually a small part of the whole because there has to be circumstances, timing, your upbringing, your culture and opportunities—all these things have to line up or you are not a success . . . [Whether] you are a success or failure is not mainly due to your hard work or lack of it . . . [It] depends on forces beyond your control.” Mary Paik Lee would be rolling in her grave just about now.

No doubt we all want to succeed but there are obstacles beyond our control, including racial discrimination for people of color, that stand in our way. Yet, the solution is rather simple: relinquish meritocracy. This isn’t because McIntosh recommends it but rather Scripture demands it: “What do you have that you did not receive? And if you did receive it, why do you boast as though you did not?” (1 Cor. 4:7). Recognize that what we have is not earned but God, in His inexplicable grace, gave to us. Sure, we work hard to reach our goals, believing with every ounce of our being that “all hard work brings a profit” (Prov. 14:23), but so did many others who, for reasons outside of their control, couldn’t get there. Only then will we see, as DiAngelo points out, the futility of congratulating ourselves on our success, and, instead of snubbing those who are still on the outside looking in, we will be “generous on every occasion” (1 Cor. 9:11).

As for those feeling overwhelmed by obstacles beyond their control, you also must renounce something: the idea that working hard is a means to get ahead. Rather, accept that working hard is the end in itself. This, of course, is a ridiculous concept unless you believe in the God of the Bible who demands stewardship of what has been entrusted—whether little or much is irrelevant—to us. What is relevant is that God will “settle accounts with [us]” on the judgment day, not based on how much we gained (which can be done in ungodly manners) but that we worked faithfully, regardless of whether it resulted in a profit (1 Cor. 4:2; 2 Tim. 4:16).

So, I break with DiAngelo who insinuates that incentivizing working hard is unavoidably a racial ideology. It could be but not intrinsically, especially for those who believe in God. We work diligently to honor God who values work itself. Note that it was before the fall that God “put [the first human] in the Garden of Eden to work it and take care of it” (Gn. 2:15). Our incentive is to glorify such God with diligent labor, whether manual or intellectual. Only then we hope to be that “hardworking farmer” [who is] the first to receive a share of the crops” (e.g., Lee's family; 2 Tim. 2:6). If not, we'll be okay, in time, knowing that God was pleased with our faithfulness.

And because we recognize that the playing field hasn’t quite leveled yet—but certainly not anywhere near the level of pre-Civil Rights era—the advice of Stephen Carter, a long-tenured Black law professor at Yale, should be heeded by all, not just people of color. He said, “It would not be a bad thing at all for us as a race to develop as our defining characteristic: Oh, you know these Black people, they always work twice as hard as everybody else.” Mary Paik Lee would have nodded her head in approval while also seeking changes.

Posted in AMI Blog

Recent

What I Won’t Say to the Lord in My Prayer for Healing of Pastor Eddie

January 25th, 2023

How Would You Respond to Those Who Say, “You Cannot Trust the Gospel Accounts?"

September 2nd, 2022

Should the Church Celebrate, Lament or Be Silent Over the Recent Abortion Verdict?

July 1st, 2022

“Contradictions” in the Bible: How Do I Make Sense of Them?

June 22nd, 2022

Is There Hope for Ukrainian Refugees?

April 5th, 2022