Whiteness: Is This Something Only White People Can Perpetrate?

Written by P. Ryun Chang

Disclaimer: My view expressed here does not necessarily represent the respective views of other AMI pastors.

After seeing a full-page photo of Rev. Martin Luther King’s casket on the front page of Presbyterian Survey, a White reader, presumably a Christian from the South, wrote: “I am a segregationist 100 percent...it is a matter of their [Black people] sorriness, laziness and lack of self-pride and not enough gumption to get out and work for what they want.” Such virulent racism of the past is a stark contrast to the subtler racism of today—often referred to as “whiteness”/“white privilege”/“white supremacy.” What do these terms mean? Can people of color also be guilty of whiteness?

The origin of whiteness is explained in the seminal work, "The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race" (2010), by Willie James Jennings, a Black theologian and professor at Yale Divinity School. Let’s first explore Jennings’ main argument: "Whiteness is co-creator with God.” For Africans in the pre-colonial era, their “sense of identity [came] directly from the land” (49); their “ways of life . . . [were] patterned not after but actually with space, with land (50). They intuitively knew when to hunt and gather (“around periods when the heat of the savannah was bearable”), could “track a hyena across a wide slab of bare rock,” and “identify edible buried plants by only a bit of grass” (49). In this manner, the land served “as primary signifiers of [their] identity” (59).

Everything changed when the European colonists arrived. They saw this arrangement as “the instability of both land and people,” cleared and organized “the land, wetlands, fields, and forests” and “brought [the African people] into productive civilization” (61). But this reconfiguration led to the “the loss . . . of a life-giving collaboration of identity between place and...people” (63). In place of land, “Europeans established a new organizing reality for identities: themselves,” meaning that “whiteness replaced the earth as the signifier of identities.” Subsequently, “a scale was formed: white, almost white, mixed, and black,” and “being White placed one at the center.” The identity and significance of non-Whites was determined “by proximity to and approximation of White bodies.” The darker the skin, the more one was marginalized (58-59).

This is the origin of race as a concept in which whiteness becomes a co-creator with God. European colonialists—as an oppressive, not collaborative, signifier—recreated Africa by their “power to change the native worlds, to reconfigure space, uproot peoples and replant them” (62). In this skewed relationship, the identity of Africans and the significance of their work “gets channeled through White presence" (60): you are what White people say you are; the significance of your action is contingent upon White validation. The power that White people possessed to signify Black people to such an unbounded degree was their privilege and supremacy.

At the outset, whiteness in America was characterized by brutality‚ as evidenced by chattel slavery, Black codes, and Jim Crow segregation. But largely due to progressive reforms initiated in the mid-1960s, James E. Blackwell, a Black sociologist, noted in "The Black Community: Diversity and Unity" that by the 1980s “it would be ...misleading to deny the progress, albeit limited, that Blacks have made toward achieving equality and full participation as citizens” (1).

Yet many Black people still feel the scourge of whiteness. Many who claim solidarity with the Black community ironically do so while utilizing their position of whiteness. A Black colleague was not impressed by John Piper, a well known White pastor, when he publicly supported Lecrae, a Black Christian hip-hop artist who prominently stepped back from “White evangelicalism.” Rather than eagerly giving his stamp of approval facing his majority-White audience, she said it would have been better had Piper first “listened and learned.” (Agreed, as long as dialogue is allowed at some point).

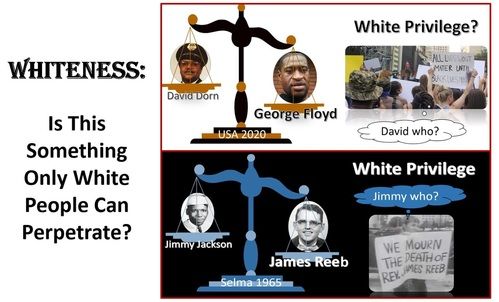

We can see the subtlety of whiteness traced back to 1965, when James Reeb, a White minister from Boston was killed by White supremacists while protesting in Selma. Among the White people in the North who were otherwise mildly sympathetic at best, his murder immediately “provoked a national outcry and demonstrations in many cities,” which prompted Reeb’s White colleague to admit, “we finally woke up and it was Jim’s death that woke us up.”

In response, “some Blacks felt bitter that the killing of the White minister had stirred a nation unmoved by the death of Jimmy Jackson,” a Black man killed earlier while peacefully protesting in Selma. Stokely Carmichael, a leader of the movement noted that “it almost [seems that] for this to be recognized, a White person must be killed; the movement itself is playing into the hands of racism” (Williams 1988:275).

This wasn’t the blatant kind of whiteness that brutalized Blacks, but rather a subtle one in which Black significance was still contingent upon White validation—conferred only when a White, not Black, person died. This meant that even the sympathetic Whites of the 1960s did not signify Black life with the same value bestowed on Whites; their subtle whiteness came with condescension that debased Blacks.

This doesn’t differ much from the “woke” people of today who, while proclaiming that Black Lives Matter, ignore the deaths of certain Black people, perhaps because they don’t fit the BLM narrative. Consider the death of David Dorn, a retired Black policeman who was gunned down by a rioter while protecting his friend’s store. His death was ignored similarly to the death of Jimmy Jackson in the 1960s.

If Black Lives Matter is fundamentally about the sacredness of Black life itself, then White people privileging the death of one Black person (George Floyd) over another Black person (David Dorn)—both VICTIMS of INJUSTICE—based solely upon the skin color of their respective perpetrators, is an example of subtle whiteness that continues to dehumanize Blacks.

What are we to do with this lingering whiteness? First, ask whether whiteness is an offense that only White people can commit. Of course, if this matter is exclusively about race—Whites seeing Blacks as inferior because the latter aren’t white enough—then, yes, this is an offense only White people can commit.

But the forerunner to whiteness was all about power; race didn’t amplify it as we are witnessing now. Consider the genesis of slavery. In "Racial and Cultural Minorities: An Analysis of Prejudice and Discrimination" (5th ed., 2013), Simpson and Yinger note that “most of the ten or eleven million people taken from Africa, mostly to be sent to the New World, were prisoners of war, sold by Africans to European agents” (48). And while rare, a few of these oppressed slaves became oppressors themselves in the New World. “In the seventeenth century a Virginia court had upheld the right of one [Black man] to claim the perpetual service of another Black [man]” (48).

Note that in these contexts, slavery had nothing to do with race but everything to do with power. Yet they had all the earmarks of whiteness: centering oneself, oppressive domination at worst (virulent whiteness), or paternalism at best (subtle whiteness). In the same way brands like Xerox or Kleenex became common verbs/nouns to denote “to copy” or “soft tissue,” whiteness as a common noun denotes domination and condescension while whiteness as a proper noun refers to what Whites have done to Blacks.

Subsequently, the line that separates oppressors from the oppressed can become blurry when power overshadows race (e.g., non-Whites in positions of power dominating or acting with condescension toward weaker White people) or when race is a non-factor (e.g., involving only non-Whites). In this way the oppressed in the past can be oppressors today; the oppressors of today can be oppressed tomorrow.

Consider whether whiteness as a common noun is an offense, which dehumanizes humans who bear God’s likeness, that any person can commit, not just Whites. Biblically, at the core, “whiteness” is a human problem because of our separation from a holy Creator because of sin. Rendered weak and wicked as a result, all humans, regardless of skin color, can easily succumb to the allure of power (Mt. 20:25) because it gives us a false sense of strength and exclusivity.

Today, oppression and race are interwoven in dialogue, and rightly so; while in Houston, I attended a march that deeply set in the reality for me that George Floyd, while not a saint, was a man created in God’s likeness, oppressed brutally in his final moment by a cruel oppressor.

In Christ, we fight “whiteness” by refusing to base our identity on how Black/White/Brown/Yellow people define us. We base our identity on who God calls us to be and follow in Christ’s steps “who did not come to be served but to serve” the weak and wicked (Mk. 10:45).

Let us remember that Christ signifies the oppressed and oppressors, both sinners before God in desperate need of His grace, with a new identity through his atoning sacrifice: “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation: the old has gone, the new has come (2 Cor. 5:17).

After seeing a full-page photo of Rev. Martin Luther King’s casket on the front page of Presbyterian Survey, a White reader, presumably a Christian from the South, wrote: “I am a segregationist 100 percent...it is a matter of their [Black people] sorriness, laziness and lack of self-pride and not enough gumption to get out and work for what they want.” Such virulent racism of the past is a stark contrast to the subtler racism of today—often referred to as “whiteness”/“white privilege”/“white supremacy.” What do these terms mean? Can people of color also be guilty of whiteness?

The origin of whiteness is explained in the seminal work, "The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race" (2010), by Willie James Jennings, a Black theologian and professor at Yale Divinity School. Let’s first explore Jennings’ main argument: "Whiteness is co-creator with God.” For Africans in the pre-colonial era, their “sense of identity [came] directly from the land” (49); their “ways of life . . . [were] patterned not after but actually with space, with land (50). They intuitively knew when to hunt and gather (“around periods when the heat of the savannah was bearable”), could “track a hyena across a wide slab of bare rock,” and “identify edible buried plants by only a bit of grass” (49). In this manner, the land served “as primary signifiers of [their] identity” (59).

Everything changed when the European colonists arrived. They saw this arrangement as “the instability of both land and people,” cleared and organized “the land, wetlands, fields, and forests” and “brought [the African people] into productive civilization” (61). But this reconfiguration led to the “the loss . . . of a life-giving collaboration of identity between place and...people” (63). In place of land, “Europeans established a new organizing reality for identities: themselves,” meaning that “whiteness replaced the earth as the signifier of identities.” Subsequently, “a scale was formed: white, almost white, mixed, and black,” and “being White placed one at the center.” The identity and significance of non-Whites was determined “by proximity to and approximation of White bodies.” The darker the skin, the more one was marginalized (58-59).

This is the origin of race as a concept in which whiteness becomes a co-creator with God. European colonialists—as an oppressive, not collaborative, signifier—recreated Africa by their “power to change the native worlds, to reconfigure space, uproot peoples and replant them” (62). In this skewed relationship, the identity of Africans and the significance of their work “gets channeled through White presence" (60): you are what White people say you are; the significance of your action is contingent upon White validation. The power that White people possessed to signify Black people to such an unbounded degree was their privilege and supremacy.

At the outset, whiteness in America was characterized by brutality‚ as evidenced by chattel slavery, Black codes, and Jim Crow segregation. But largely due to progressive reforms initiated in the mid-1960s, James E. Blackwell, a Black sociologist, noted in "The Black Community: Diversity and Unity" that by the 1980s “it would be ...misleading to deny the progress, albeit limited, that Blacks have made toward achieving equality and full participation as citizens” (1).

Yet many Black people still feel the scourge of whiteness. Many who claim solidarity with the Black community ironically do so while utilizing their position of whiteness. A Black colleague was not impressed by John Piper, a well known White pastor, when he publicly supported Lecrae, a Black Christian hip-hop artist who prominently stepped back from “White evangelicalism.” Rather than eagerly giving his stamp of approval facing his majority-White audience, she said it would have been better had Piper first “listened and learned.” (Agreed, as long as dialogue is allowed at some point).

We can see the subtlety of whiteness traced back to 1965, when James Reeb, a White minister from Boston was killed by White supremacists while protesting in Selma. Among the White people in the North who were otherwise mildly sympathetic at best, his murder immediately “provoked a national outcry and demonstrations in many cities,” which prompted Reeb’s White colleague to admit, “we finally woke up and it was Jim’s death that woke us up.”

In response, “some Blacks felt bitter that the killing of the White minister had stirred a nation unmoved by the death of Jimmy Jackson,” a Black man killed earlier while peacefully protesting in Selma. Stokely Carmichael, a leader of the movement noted that “it almost [seems that] for this to be recognized, a White person must be killed; the movement itself is playing into the hands of racism” (Williams 1988:275).

This wasn’t the blatant kind of whiteness that brutalized Blacks, but rather a subtle one in which Black significance was still contingent upon White validation—conferred only when a White, not Black, person died. This meant that even the sympathetic Whites of the 1960s did not signify Black life with the same value bestowed on Whites; their subtle whiteness came with condescension that debased Blacks.

This doesn’t differ much from the “woke” people of today who, while proclaiming that Black Lives Matter, ignore the deaths of certain Black people, perhaps because they don’t fit the BLM narrative. Consider the death of David Dorn, a retired Black policeman who was gunned down by a rioter while protecting his friend’s store. His death was ignored similarly to the death of Jimmy Jackson in the 1960s.

If Black Lives Matter is fundamentally about the sacredness of Black life itself, then White people privileging the death of one Black person (George Floyd) over another Black person (David Dorn)—both VICTIMS of INJUSTICE—based solely upon the skin color of their respective perpetrators, is an example of subtle whiteness that continues to dehumanize Blacks.

What are we to do with this lingering whiteness? First, ask whether whiteness is an offense that only White people can commit. Of course, if this matter is exclusively about race—Whites seeing Blacks as inferior because the latter aren’t white enough—then, yes, this is an offense only White people can commit.

But the forerunner to whiteness was all about power; race didn’t amplify it as we are witnessing now. Consider the genesis of slavery. In "Racial and Cultural Minorities: An Analysis of Prejudice and Discrimination" (5th ed., 2013), Simpson and Yinger note that “most of the ten or eleven million people taken from Africa, mostly to be sent to the New World, were prisoners of war, sold by Africans to European agents” (48). And while rare, a few of these oppressed slaves became oppressors themselves in the New World. “In the seventeenth century a Virginia court had upheld the right of one [Black man] to claim the perpetual service of another Black [man]” (48).

Note that in these contexts, slavery had nothing to do with race but everything to do with power. Yet they had all the earmarks of whiteness: centering oneself, oppressive domination at worst (virulent whiteness), or paternalism at best (subtle whiteness). In the same way brands like Xerox or Kleenex became common verbs/nouns to denote “to copy” or “soft tissue,” whiteness as a common noun denotes domination and condescension while whiteness as a proper noun refers to what Whites have done to Blacks.

Subsequently, the line that separates oppressors from the oppressed can become blurry when power overshadows race (e.g., non-Whites in positions of power dominating or acting with condescension toward weaker White people) or when race is a non-factor (e.g., involving only non-Whites). In this way the oppressed in the past can be oppressors today; the oppressors of today can be oppressed tomorrow.

Consider whether whiteness as a common noun is an offense, which dehumanizes humans who bear God’s likeness, that any person can commit, not just Whites. Biblically, at the core, “whiteness” is a human problem because of our separation from a holy Creator because of sin. Rendered weak and wicked as a result, all humans, regardless of skin color, can easily succumb to the allure of power (Mt. 20:25) because it gives us a false sense of strength and exclusivity.

Today, oppression and race are interwoven in dialogue, and rightly so; while in Houston, I attended a march that deeply set in the reality for me that George Floyd, while not a saint, was a man created in God’s likeness, oppressed brutally in his final moment by a cruel oppressor.

In Christ, we fight “whiteness” by refusing to base our identity on how Black/White/Brown/Yellow people define us. We base our identity on who God calls us to be and follow in Christ’s steps “who did not come to be served but to serve” the weak and wicked (Mk. 10:45).

Let us remember that Christ signifies the oppressed and oppressors, both sinners before God in desperate need of His grace, with a new identity through his atoning sacrifice: “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation: the old has gone, the new has come (2 Cor. 5:17).

Recent

What I Won’t Say to the Lord in My Prayer for Healing of Pastor Eddie

January 25th, 2023

How Would You Respond to Those Who Say, “You Cannot Trust the Gospel Accounts?"

September 2nd, 2022

Should the Church Celebrate, Lament or Be Silent Over the Recent Abortion Verdict?

July 1st, 2022

“Contradictions” in the Bible: How Do I Make Sense of Them?

June 22nd, 2022

Is There Hope for Ukrainian Refugees?

April 5th, 2022